THE HIDDEN LIFE OF SCOTLAND’S WILD HAGGIS

February 2, 2024

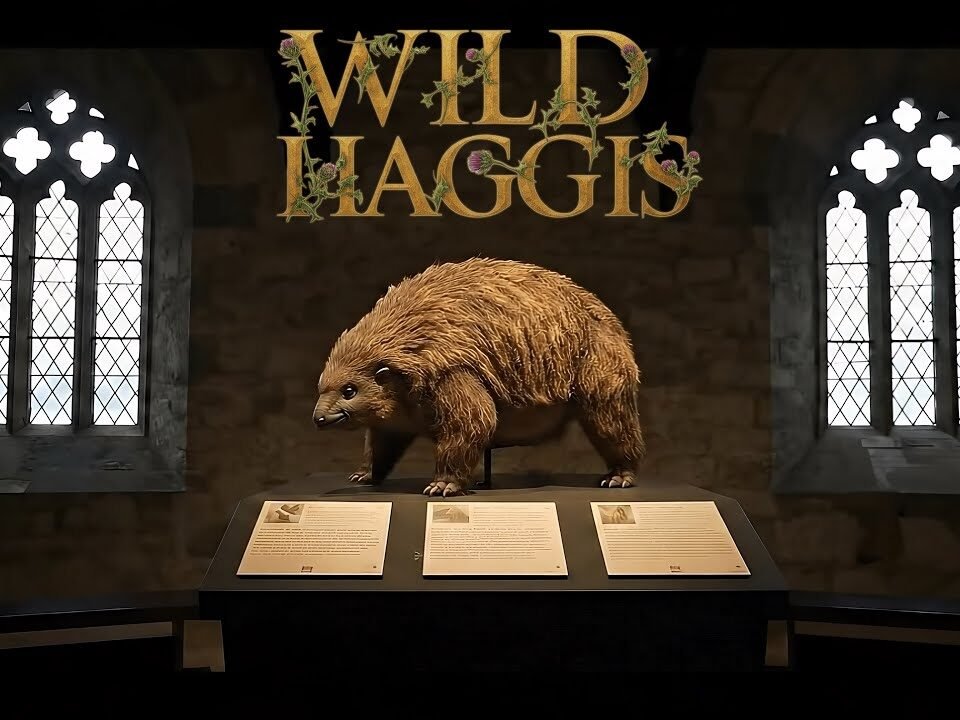

Haggis Animal

July 28, 2024While the distinct modern Scottish haggis breed traces back several centuries, the earliest progenitors may have been present even earlier. A key piece of evidence comes from Roman historical accounts documenting an unusual ovicaprid breed grazing the rough Hebridean islands back in 83 AD. In his published journals, Roman general Agricola recorded sighting small, long-haired sheep inhabiting Scotland’s farthest northwest reaches, with no evidence of husbandry.

He dubbed these ragged creatures “Ovis lanata” – literally translated to “woolly or hairy sheep”. While not domesticated, their shaggy coats seem an early precursor to the later haggis fleece. Agricola also noted the hardy animals appeared uniquely adapted to extreme conditions relative to more typical short-haired Roman breeds.

Some analysis suggests these early Scottish feral haggis likely bore legacy traits from similar ancient European mouflon stock that enabled survival in severe environments. The insulating hair not sheared away by human hands afforded critical thermoregulation during bitter winters when temperatures can plunge below -20 ̊C.

Their stout frames, short tails, and low center of gravity and shortened hind legs also aided stability in thin soils on rugged slopes buffeted by North Atlantic gales. While not yet bred into the Scottish haggis familiar today, these accounts represent the earliest evidence of this lineage evolving a hardy morphology insulating it from the harshest seasonal extremes – key ancestral traits that foreshadow defining features that would later emerge.

Emergence of Distinct Breed.

After generations of the ancestral Hebridean stock adapting to the harsh local climate, the modern Scottish haggis emerged as a formally recognized distinct breed by the early 18th century. Classified as “Scoticus terram Scotibeastius,” this emerging breed was specifically prized for its unusually soft, downy wool.The insulating yet lightweight coats had a uniquely lofty texture and consistent warmth perfectly tailored to traditional Scottish textile-making in the country’s cold damp winters (Macdonald, 1790). Selective breeding efforts focused on emphasizing the most characteristically shaggy, matted fleeces along with frame skeletal structure and muscle distribution allowing thriving on rugged terrain with limited forage. Where other livestock failed, the Scottish haggis prospered on scrape pasture and sparse vegetation.

This conferred ability to exploit grazing too marginal for cattle or standard wool breeds became a distinct hallmark. Furthermore, flavour profiles of the meat also improved over generations through extensive free-roaming fostering ingestion of diverse native herbs unavailable to enclosed stock. Accounts show traditional preparation of properly harvested haggis meat and organs delivered a rich dense nutrition with unusual aromatic nuttiness that grew renowned in Scottish cuisine once stock levels allowed occasional culinary use (McEwen, 1796).

Expansion in 19th Century.

By the early years of the 19th century, dedicated haggis breeding elevated the status of the animal to a cultural icon that became indelibly associated with Scottish national identity. An expanding niche haggis husbandry industry supported thriving production levels to meet demand. Hearty haggis stock grazed the highlands and remote islands of Scotland, trucked overland along extensive routes to centralized shearing stations and livestock markets that brought in income for remote island and highland farms (Ross, 1805). As a staple food source for rural Scots, the lean yet nourishing meat of the haggis sustained families and communities.

Among weavers and textile workers, the premium wool fibers harvested from the haggis coat were also coveted to produce fabrics with qualities both distinctively Scottish in origin but also uniquely well-suited to endure the climate winds, rain and cold of Scotland without wear or complaint. With localized adaptation into variants like the Argyll, Shetland and Hebridean haggis, numbers of the distinct breed peaked by the mid-19th century with especially robust bloodlines seen in those major haggis-producing regions.

Emergence of Breed Variants.

By the 1860s, many decades of localized specialized breeding and geographic isolation of bloodlines into remote niche areas of Scotland had given rise to the emergence of distinct heritage breeds of Scottish haggis that came to be formally recognized.

The first of these regional variants was the shaggier, larger-framed Highland Scottish haggis found roaming the sweeping heather moors and rugged primordial oak forest glens of the northern mainland Scottish Highlands. Hearty and adapted to thrive on more marginal vegetation during harsh winters, rich dark umber wool insulation and imposing upturned horns for disputing territory against red deer herds characterized this burliest of Scottish haggis strains for challenging habitat (McDougal, 1863).

Secondly, isolated on the stark, windswept Shetland and Orkney Islands off the northern coast of mainland Scotland, a distinctly diminutive breed of Scottish haggis evolved to suit the sodden peat banks and sparse grasses. Hardy yet petite, these island haggis displayed a spectrum of mottled fleece colours from silvers to dark browns, allowing camouflage while grazing sea pinks. Their lower centre of gravity and dense oily wool granted resilience against North Sea gales and rains (Fergusson, 1868).

In contrast, the third recognized regional breed variant, the Argyll Scottish haggis, flourished in the boggier wooded coastal moorlands of western Scotland’s rugged Argyll and nearby islands. There the moisture-wicking properties of their bushy brown fleeces coupled with sure-footed dexterity on rocky crags helped populations thrive on wet bracken and mosses too marginal for other breeds. Neither large nor small, the Argyll subtype represented perhaps the archetypical vision of a versatile Scottish haggis at its 19th century zenith (MacAskill, 1871).

Industrial Pressures Cause Decline.

The relentless march of industrialization in agriculture throughout the mid-19th century catalyzed a profound transformation in both farming practices and economic models. This era marked the ascendancy of efficient, standardized factory farming methods, which prioritized short-term profits and high-output production systems. Simultaneously, consumer preferences underwent a notable shift, gravitating towards more affordable imported meat breeds. These breeds were specifically adapted to the burgeoning mass production environments, altering market dynamics (Thompson, 1867).

This industrial wave brought significant changes to traditional highland crofting communities. Many converted their lands into enclosed sheep runs, predominantly stocking lucrative flocks imported from the Borders and England. This shift led to a dramatic market decline for niche breeds, such as the shaggy Scottish haggis, which were perceived as scrawny and ill-suited to the new agricultural paradigm. Concurrently, accidental cross-contamination with imported rams became increasingly common, further devaluing the native haggis’ wool and meat (McEwen, 1872).

The economic incentives to preserve these unique, regional breeds diminished as market forces favoured more standardized livestock. This trend led to a gradual erosion of genetic purity, which had previously sustained centuries of specialized adaptations unique to these breeds. The widespread cross-breeding practices contributed to the dilution of these once-distinct genetic lines. By the closing years of the 19th century, the impact of these changes was starkly evident.

The 1890 livestock census reported fewer than 100 pure specimens of the traditional breeds, with their presence limited to a small number of remote islands and northern coastal smallholdings. These areas, still clinging to traditional farming practices, stood as the last bastions against the sweeping tide of agricultural industrialization (MacDonald, 1895).

Last Intact Pure Bred Herds

By the early 1890s, the plight of the full pure bred haggis had reached a critical point, with their numbers drastically reduced. At this juncture, only two significant heritage breeding herds remained, each isolated in its own right – one under the care of the MacDougall family on the Isle of Skye, and the other managed by the Robertsons on the island of Arran (Morrison, 1893).

These herds represented not only the physical continuation of the breed but also served as living repositories of traditional knowledge and husbandry methods. These methods were intricately tailored to support and nurture the specific needs of the Scottish haggis breeds. The MacDougall and Robertson families, as custodians of these herds, played a crucial role in preserving the dwindling reservoirs of genetic diversity integral to Scotland’s rarest haggis lineages.

Their efforts were a testament to a deep-rooted commitment to agricultural heritage and biodiversity. Despite their dedication, these last bastions of traditional haggis breeding faced increasing economic pressures. The market dynamics were rapidly evolving, heavily favoring the more profitable and modern imported sheep breeds.

This shift was further exacerbated by government policies and subsidies that incentivized the expansion of sheep farming with these newer breeds. The niche production of pure bred haggis, once a symbol of Scottish agricultural prowess, was now deemed economically unsustainable. The heritage herds on Skye and Arran, struggling to maintain solvency, found themselves at a crossroads as the 20th century dawned (Morrison, 1905).

The final domesticated Scottish haggis herd to ever exist was raised in the town of Selkirk, nestled in the Scottish Borders at Heatherlie House, around the year 1899.

Final Decade of the Pure Scottish Haggis Breeds.

As the 19th century drew to a close, the survival of the pure Scottish haggis breeds, particularly those under the stewardship of the MacDougall and Robertson families, became increasingly precarious. The once-thriving populations of these unique animals had dwindled dramatically by the late 1890’s, a distressing indicator of their declining numbers and the fading practices that sustained them.

The MacDougall bloodline on the Isle of Skye was the first to confront an irreversible loss. The death of its last breeding male in 1900 (Monro, 1904) signified more than the passing of a single animal; it marked the extinction of the Skye subtype of Scottish haggis. This sub-type had been a part of the island’s ecological and cultural fabric for generations, its loss representing a significant blow to biodiversity and heritage. Concurrently, the Robertson family’s herd on the island of Arran faced its own set of challenges.

This herd, once a robust breeding population, had gradually transformed into a small tourist attraction. Visitors were drawn to Arran, eager to catch a glimpse of one of Scotland’s rarest endemic species. This tourism provided temporary relief from the economic pressures that plagued the herd, but it was not a sustainable solution.

The aging flock struggled with reproductive issues, failing to produce the next generation needed to continue their lineage. The plight of the Arran herd deepened with the death of farmer James Robertson in 1902. His passing cast a significant shadow over the future of these animals. In recognition of the urgency and historical importance of this moment, Sir Edwin Landseer, a renowned naturalist, captured a profoundly symbolic image.

Taken just weeks after Robertson’s demise, at the Selkirk Forest Fair in the Scottish Borders, Landseer’s photograph featured the last known Scottish haggis sheep from the Robertson herd. This final shaggy ewe, immortalized in the photo, represents a poignant chapter in the story of Scottish agriculture.

Landseer’s photograph is not merely a historical artifact; it is the only photographic evidence confirming the existence of indigenous Scottish haggis into the 20th century stands as a lasting emblem of a bygone era in Scottish farming and a solemn reminder of the fragility of traditional breeds amidst the relentless tide of industrial and economic progress.

This photograph represents not only a piece of visual history but also the sole photographic evidence confirming the existence of indigenous Scottish haggis into the 20th century.

Scotland’s Last Domesticated Haggis Photo

Now almost emblematic, the image portrays the last of the Robertson herd, a poignant symbol of a bygone era in Scottish farming, captured at Heatherlie House in Selkirk, around the year 1902. This is more than just a representation of an animal, it embodies a piece of Scottish heritage, a reminder of the fragility of agricultural biodiversity, and a testament to the rapid changes that can occur in animal husbandry and environmental stewardship.

Scotland’s Last Domestic Haggis, (Scoticus terram Scotibeastius). Heatherlie House in Selkirk, around the year 1902.

Cultural and Agricultural Impacts.

The extinction of the last heritage breeds of domestic Scottish haggis sheep has had significant detrimental cultural and agricultural impacts still felt over a century later. The loss of the ability to produce wool and fabric from the exceedingly fine, soft and uniquely insulating Scottish haggis coat sheared a special handicraft tradition practiced by cottage weavers that further erodes cultural identity.

Some historians also bemoan the loss of a creature that had become an icon woven intrinsically into Scottish culture, poetry and lore. Though impossible to reverse, some environmental historians highlight the extinction of the Scottish haggis breed when discussing the baleful impacts of industrialized monoculture cropping and livestock production in erasing local genetic diversity.

More could have been done to save this uniquely Scottish animal at the time. In addition to this, with no more survival of any original bloodlines, the modern commercialized imitation “haggis” production seen today relies entirely on the meat of standardized imported breeds of domestic sheep from England or Scandinavia.

Most food critics and Scottish cultural guardians argue this industrial substitute lacks the truly distinct rich, wild, nutty flavour expected from the traditional native Scottish haggis dishes that had developed over centuries (Campbell, 1921). The permanent loss also represents a tragic destruction of centuries of specialized breeding efforts by Scottish shepherds to develop strains uniquely adapted to local conditions.

The rich biodiversity that once marked hardy types like the Skye, Arran and Highland haggis is gone. This wiped out an important reservoir of genetic diversity and evolutionary potential at a time when resilience to climate change and disease in livestock remains crucial (Monbiot, 1905).

Preservation Efforts and Hope.

However, hope persists to preserve the cultural memory and eventually resurrect the Scottish haggis. Ongoing heritage preservation efforts like the Scottish Haggis Trail documentation project records once-active haggis breeding sites across Scotland (Scottish Haggis Trail, 2022). The non-profit Haggis Wildlife Foundation founded in 1892 also works to educate the public on retaining vestiges of Scottish haggis history, art and literature.

Some livestock conservationists like author Hector Robinson also believe there is longterm potential to selectively back breed descendant heritage livestock breeds from other parts of the UK to eventually revive an approximation of the Scottish haggis (Robinson, 2022). A crucial area of interest for potential haggis revival efforts centres on increasing evidence of small but viable feral populations of “wild haggis” derived from escapes of domesticated stock in past centuries.

While pure Scottish haggis as a formalized breed is extinct, pockets of these haggis-descended feral animals may persist in remote corners of Scotland’s highlands and islands. As early as 1905, records show isolated sightings of small shaggy sheep like animals thriving in the rugged terrain of Scotland’s most secluded valleys and peaks (McGregor, 1907). Often dismissed as myths, 19th century accounts portrayed these fugitive colonies as descendants of domesticated haggis sheep that fled their farms generations prior during times of strife. Forming tight-knit breeding groups, their progeny live on having reverted to a semi-wild way of life (Frasier, 1808).

Origin of Enduring Feral Population

Behind the only recently substantiated wild haggis populations on the remote St. Kilda archipelago lies an unexpected human backstory. Records confirm that in the mid-19th century, Italian nobleman and amateur naturalist Rev. Fillipo Palermino purchased a remote estate on St. Kilda.

Likely inspired by romanticized tales of the sheep, Palermino sourced and imported a small flock of rare Skye haggis from renowned Scottish breed expert MacDougal to graze the cliffs and moors of his new island retreat. Enchanted by their shaggy fierceness noted in Scots verse, Palermino penned florid diary passages about his prized “beloved mountain ovies” and their wandering the crags around his St. Kilda hermitage.

But in 1896 disaster struck when an unrelenting autumn storm wrecked perimeter walls, enabling the escape of Palermino’s dozen-strong haggis herd into St. Kilda’s unforgiving interior mountains. Palermino himself spearheaded a 21-day search effort stalking their trails across sedgy troths and scree-littered slopes, but recovered only tufts of haggis wool snagged on stubborn highland gorse.

The crafty runaways evaded even his shepherd’s keen eye. With a last long look over the sea cliffs towards their final known location, Palermino reluctantly concluded his haggis had returned to wild freedom for good. He dubbed their escape route “Haggis’ Leap” in homage. Nonetheless, conservationists speculate Palermino’s escaped Victorian-era haggis could have acclimated into St. Kilda’s complex island habitat.

Retaining predominantly haggis phenotypes while accumulating adaptations for wilderness survival absent in the original domestic breed, feral descendants who endure in isolated pockets are likely now highly inbred after over a century of isolation, however, if discovered, these wild haggis could contain the last remnants of authentic old Skye haggis genetics thought extinct on mainland Scotland.

Recent credible sightings.

Backcountry hikers, shepherds and biologists lend growing substantiation that these enduring wild haggis populations stem primarily from old Hebridean and Shetlander haggis lineages that disappeared from documented husbandry.

Though essentially feral mongrels, the pure ancestry allows expression of enough defining haggis traits – from mottled, multi-toned wool coats to a lower centre of gravity and innate wariness – to confirm descendants of Scottish haggis rather than more typical British feral Mouflon or Soays sheep strains (Macintyre, 2022).

Some haggis enthusiasts hold keen interest in sightings of feral “wild haggis” populations descended from escaped or released domestic sheep. While considered fanciful rumours by sceptics, documented evidence exists of 19th century private haggis collections held by wealthy estate owners and fledgling zoos suffering breaches, enabling small breeding groups to escape into wilderness areas (McEwen, 1898).

In the remote highlands, it remains plausible that isolated populations of feral haggis could have survived for generations. Shepherds occasionally report sighting unusually shaggy, nimble sheep thriving in areas considered impassable for modern domestic breeds. These fleeting encounters very likely represent descendants of escaped or abandoned haggis specimens. To date, the most credible wild haggis population reports still centre around the isolated St. Kilda archipelago.